_

CREVÉ

Jesse Darling

Solo exhibition

Curated by Céline Kopp

March 15 — June 2nd, 2019

Opening: Friday 16 March from 6:00–10:00 P.M.

Panorama

Friche la Belle de Mai

41, rue Jobin

13003 Marseille

Co-production SCIC Friche la Belle de Mai.

With support of Fluxus Art Projects and Lafayette Anticipations - Fondation d'entreprise Galeries Lafayette.

Special thanks: Mucem, Hôtel La Résidence, Galerie Sultana, Paris.

Triangle France - Astérides is pleased to announce CREVÉ, Jesse Darling’s first institutional solo exhibition in France. Literally meaning ‘punctured’ in French, the title evokes an intimate and general feeling of exhaustion and introduces a reflection on failing structures of power and knowledge. The works in the exhibition, some of which newly produced, attempt to visualise the precariousness of architectural, cultural, and corporeal bodies as a form of wounded optimism, where nothing is too big to fail.

Jesse Darling lives and works in Berlin and London and has received commissions from the Volksbühne, Berlin, MoMA Warsaw and The Serpentine Gallery, London amongst others. They recently presented their first institutional solo exhibition in the U.K Art Now: Jesse Darling: The Ballad of Saint Jerome at Tate Britain. Jesse Darling’s work has been previously exhibited in France with a solo exhibition at Galerie Sultana, Paris (2017), and in 2018 the occasion of À Cris Ouvert, 6th edition of Les Ateliers de Rennes - contemporary art biennale, curated by Céline Kopp and Étienne Bernard.

OPENING SCHEDULE

From Wednesday to Friday, 2:00–7:00 P.M.

Saturday & Sunday, 1:00–7:00 P.M.

ADDRESS

4th floor - Panorama

Friche la Belle de Mai

41 rue Jobin

13003 Marseille

The exhibition front desk is located on the ground floor of the Tour-Panorama.

_

CONVERSATION

Jesse Darling and Céline Kop

Jesse Darling and I first met in 2017 in a coffee shop in London to discuss a collaboration for a biennale. JD came with Lux, who was a tiny baby at the time. From what I understood, It was one of the first time the two of them were traveling. That’s always a big challenge…and especially for professional meetings. I knew it because eight years earlier I was back in France to make my debut as a single parent, without much of a professional network in the country. But that’s where home and welfare were supposed to be, and I was trying to make it as young curator under these conditions.

During this meeting, as we talked about our expectations for what a biennale could be or do, JD shared the fact that their movements were currently impaired. So when we worked together, because of this and many other things we ended up having to rely on delegation and trust. The work was successful.

Back in Marseille I proposed to work together again on an exhibition. I knew for sure that JD’s work would make sense here. Marseille, as a city, offers a rare prism through which to think about our history and current context : about people’s displacements and dispossessions, about cultural resistance and assimilations, about the colonial past and its social consequences, about economical and urban transitions. And more than anything : about performativity, cleanliness, beauty, rules (and the absence of it), failures, and successes.

Obviously JD does not, and could not, speak about Marseille, but their work surely resonates with it.

The exhibition is called CREVÉ, and it was made possible through a great deal of collaboration, thanks to the labour of the people, friends, and artists working with and around Triangle France - Astérides.

Below are some exchanges that occured between Jesse Darling and myself, around the making of the exhibition.

Céline Kopp: Jesse can you tell a little bit about the title “Crevé” and where it comes from?

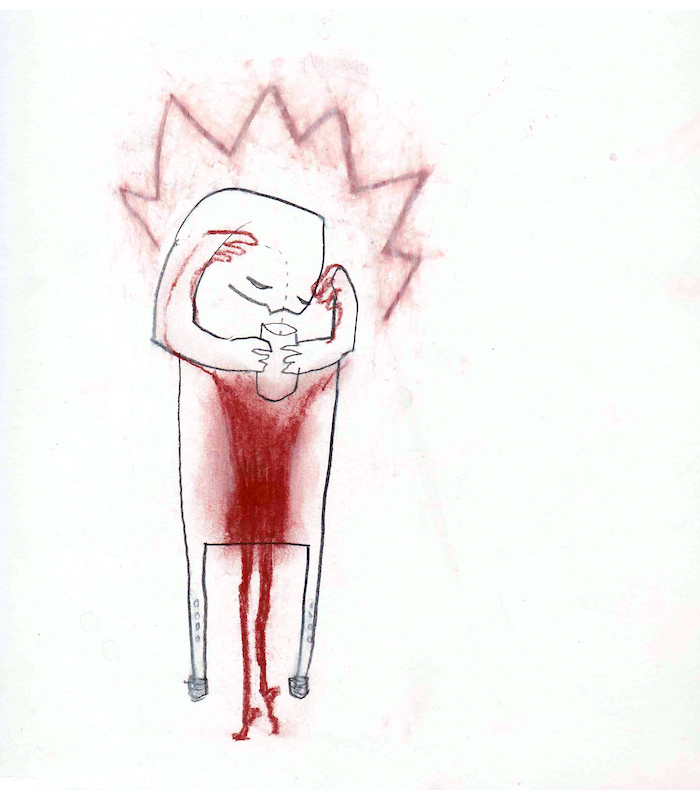

Jesse Darling: Well, you know what this means in French, yeah? Since the exhibition is in France it makes sense for the show to be titled in French but the concept really speaks to me at the moment. It’s more literal than conceptual, which means it’s how I feel right now but it also points to some formal and contextual aspects of the work. For English readers crevé is a bit like knackered, a past participle of the verb to kill (specifically, an old horse unfit for purpose). The urban dictionary defines knackered as “1. Exhausted 2. Sexually spent 3. Reprimanded 4. Broken / malfunctional.” That’s about right. Crevé means punctured, fucked. For a while now I keep making drawings in which the figures depicted have great gaping holes in them, wounds. And in many of my recent sculptures I’ve been trying to convey this sense of exhaustion and physical failure, though the failure is not total; life remains and asserts itself despite the deadness of art objects in general, or at least that’s what I’m going for. Some years ago I thought about ‘the phallic modern’ as that which cannot or must not be seen as penetrable: hermetic bodies, hermetic facade of empire. But any queer or sick body knows what it is to be full of holes, and a city like Marseille might be able to paper over its structural failures, but holes keep opening up and swallowing things and people. It’s a strong word to use but in this way it’s immediate. Why not be honest about the fact of crisis. Ongoing crisis rather than particular, but still.

C.K.: It is true that in general we try our best to keep going, to make our work seem effortless...We are never “exhausted” but always busy ; whatever one’s job, I guess. In the sense that an exhibition poster generally tries to convey a promise of success, or at least entertainment. How does the feeling (and/or physical state) of exhaustion evoked by the title translate to your experience as an artist in general? Or how does it relate to this exhibition in particular?

J.D.: About two years ago I became very ill from a neurological disease triggered by the birth of my kid. For more than a year I was paralysed down my right side and in the kind of pain that made childbirth feel like a walk in the park. Walking with a stick, couldn’t stand up, couldn’t lift my arm or use my hand. I took no parental leave and no leave of sickness. Of course there is a certain privilege inherent in this, but there is also the fact that these systems do not exist in the sector in which I make my work - let’s call it ‘the art world’ (though there are many art worlds out there and as such this universal is problematic). Knowing well the misogyny and low attention span of this art world, and as someone without a lot of generational wealth or whatever I need to work like everyone else in order to pay my rent and feed my child. I am 37 years old and had been making my work for years at this point. So when the big institution asked me to make a huge solo presentation and gave me three months to do it, I thought about it hard and then agreed. It was my first institutional show. It was on one hand an amazing opportunity to make work for the people who constitute ‘the public’ rather than ‘the art world’ - kids, older people, tourists, students, and whoever else wanders into the museum because it’s free and it’s warm. This was a great privilege and pleasure. I also knew that the people who constitute the financier class of the art world would be very likely to see it, and as such it had to be ‘good’ - ie the best, most truthful work I could make right then, with all of my heart, despite my limitations and the short time frame. I put everything into it, which is not simply a declaration of intention and focus: I postponed my physiotherapy and all my doctor’s appointments, postponed the diagnosis of other things encroaching on my body, and accrued a debt of childcare to my co-parent which had to be taken up immediately after the opening since they also need to work. The show was successful. I started to get invitations to other engagements. I turned many of these down, hoping that there would be others in the future, but some of them I felt I had to accept. My pared-down calendar tells me I will spend 4-10 days in a different city every month of the year. On my return from these cities, I care for my kid full time. “When things get settled” I am supposed to attend physiotherapy, ergotherapy. I am supposed to see the trainer who tries to prevent my developing a hunchback as the atrophied muscles gather strangely around the part of my body that keeps on working regardless, to find a therapist to help me deal with the panic attacks I keep having though I swear I am fine, just fine. But just as things start feeling stable again I am supposed to get on a plane. To install the work. To give a talk. To perform my own life, in public. And this long story in its particularities is not especially unique. When we talk on the phone, Celine, I hear your blocked nose and the cough in your throat. You’ve been working all weekend and you’re tired. I’m tired too. I try to remember to do my exercises. I WhatsApp you one evening about having this conversation. You have spent the day running around in the space trying to delegate my work, and now you are looking after your kids. It will have to be tomorrow. I spend the night in the hospital with an unexplained meningitis rash and get up early to package my drawings for the DHL guy. We talk on the phone. My kid runs in, crying. I tell her once again that I’ll be with her soon, soon.

A younger JD would have looked at this account and found it despicable and weak. Young JD, a culturally protestant matriphobic macho, was trying to survive in gendered capitalism; they found the complaint of the bourgeois class, the artist class, truly contemptible. The ultimate in first world problems. But lately I’ve been thinking about our first world problems, especially given that the first world is itself a problem. What if part of the undoing of the problem is in the acknowledgement of how racist, ableist, sexist and classist its demands and expectations? What would it look like if we admitted the inevitable failure of any body to meet these demands?

C.K.: We can acknowledge how crazy the demands are in our field in general, but what do you think about the current attention coming from institutions for works dealing with “vulnerable” bodies, or subjectivities? It seems like there is a necessary conversation to have about a structural alignment of the institution to the politics, content, and individual realities of the works on display…

J.D.: Part of the issue here is that I have spent my career (such as it is) making the case for a certain kind of fungibility. This is both the material of my work and the foundation of its making. For me this is personal as well as political. However, when fungibility is understood as the province of the Other it becomes something to be consumed rather than acknowledged in oneself. The institutions of the “art world” are just made up of people working their jobs, and some of these people are trying to do right by their artists and wider communities. But as an entity founded in structural anti-blackness, imperial violence and patriarchal distribution of resources, the “art world” favours the Barnum and Bailey model of curation, the panel discussion industrial complex, the gig economy. Artists are called upon to perform their own lives - as particular, embodied phenomena with their own name, date of birth, and profile in Dazed and Confused magazine. Embodied exemplars of whichever issue is currently at hand are unwieldy, but cheaper than art works, even allowing for fees, flights and hotel. Right now the curatorial travelling circus is stopped in the Disability part of town; everybody wants to talk about crip theory and when the sick rule the world (though when the sick rule the world, as anyone who has been really sick can tell you, there won’t be much ruling going on). I made a lot of work at one stage about my experiences of illness and its structural management, and as such I became called upon to represent disability on the institutional stage, a responsibility which I want to refuse. Firstly because of the ways in which I am disabled (living with a reactive, malfunctioning body and what a shrink would probably try to medicate as “mental illness,” as well as some previously diagnosed forms of “neurodiversity” which aren’t ever gonna get “better”) which mean that I barely manage to perform the role of artist in public. I flake out at the last minute, cancel my flight, burst into tears on stage. I am known to be “difficult,” or “unreliable.” Secondly, though, and more crucially, I want to refuse this position because of the ways in which I am not disabled: for instance, right now I can walk on my own, mount stairs, read from a text, hear, see, eat, breathe unassisted. I am the relatively able-bodied, relatively functional, white-skinned face of the difficult but fascinating idea of the disabled and dysfunctional body, and if I am to be employed as such this means that no interpreter will be necessary, no ramp will be necessary; nothing needs to change. And even though disability is really hip right now and everybody wants to book real live crips for their conference, what is being done about the stairs up to the kunsthalle and conference centre? And crucially, how can anyone expect someone who is sick to even show up in the first place? And what would it look like if that expectation wasn’t implied?

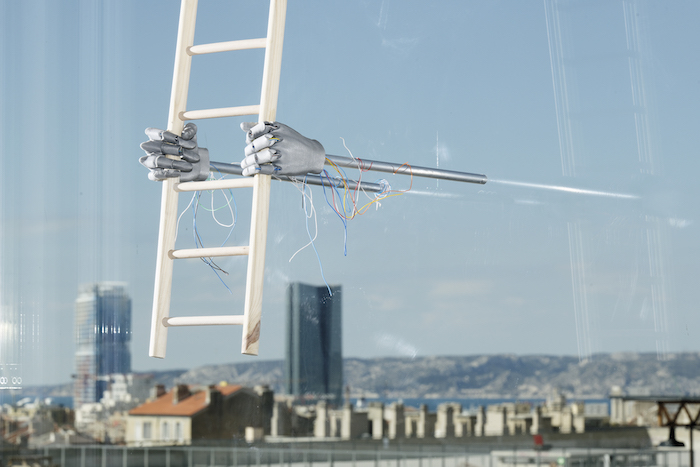

C.K.: This exhibition seems to depict the architecture, structures, and modes of display of a failing world order. Most of it is falling apart, or soon to do so. Can you say a bit about the works themselves?

J.D.: This is a show that tries to acknowledge the weight behind things assigned a certain lightness. All the planes we take; the flights to the biennale and the conference, the deportation planes, the tourist charter. The weight of administration required in the maintenance of a life. The heaviness of hours spent waiting, bodies together in space and circumstance but without conviviality. Airport lounges. Immigration offices. Hospitals. The English expression ‘feet of clay’ refers to a hidden character flaw (those who seek care, legitimacy or welfare are often implied to have a certain weakness of character). It comes from a biblical story in which Nebuchadnezzar dreams of a statue with a head of gold and feet of clay. This seems appropriate given the “holiness” of art objects, though these art objects will undermine a crucial aspect of their own holiness (i.e, their viability as commodities) through disintegrating in the space over the course of the exhibition. To place something in a vitrine is always to reenact the violence of museumification - the taxidermied corpse, the stolen artefact, the death mask dug from the ground and restored. Those flowers are the living things that stand in for my own body; it’s also a shout-out to a work made by Carolyn Lazard, called Support System (for Park, Tina and Bob). Blooming and colourful at the opening, those flowers will be starved of oxygen and dead within days (we all turn it on for the opening, right? To the extent that the inevitable depression, or exhaustion that follows a show has become completely normalised, a bipolar cycle around which I attempt to structure my working life). Their decay can be some kind of vanitas: that’s what happens to a living thing forced to perform under scrutiny for days or months at a time. But I don’t want to talk too much about the work because the work will tell its own stories without me, and without you too.

Download the conversation between Jesse Darling and Céline Kopp

Jesse Darling, Crevé, exhibition view, Triangle France - Astérides, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 2019. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

Jesse Darling, Crevé, exhibition view, Triangle France - Astérides, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 2019. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

Jesse Darling, Crevé, exhibition view, Triangle France - Astérides, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 2019. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

Jesse Darling, Crevé, exhibition view, Triangle France - Astérides, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 2019. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

Jesse Darling, Crevé,exhibition view, Triangle France - Astérides, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 2019. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

Jesse Darling, Crevé, exhibition view, Triangle France - Astérides, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 2019. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

Jesse Darling, Crevé, exhibition view, Triangle France - Astérides, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 2019. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

Jesse Darling, Crevé, exhibition view, Triangle France - Astérides, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 2019. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

Jesse Darling, Crevé, exhibition view, Triangle France - Astérides, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 2019. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

Jesse Darling, Crevé, exhibition view, Triangle France - Astérides, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 2019. Photo: Aurélien Mole.